Scholars’ Lab Fellow James Ascher went to Washington and Lee University to give a workshop in Prof. Taylor Walle’s ENGL 335 course through a Mellon-funded collaboration with the Scholars’ Lab in the UVA Library. More information about this initiative can be found here. His post is cross-listed on the W&L blog.

This post has a simple argument: if you teach novels, you should teach students to not-read novels. Now, before you get concerned, I’m not arguing against teaching literature or avoiding novels altogether; the hyphen in “not-read” means a method, not a rejection of reading. Indeed, my whole argument is based on the idea that students need help returning careful attention to texts, but faced with a deluge of texts, we teachers ought to show them how some professional literary critics not-read, or as others call it “distant read.”

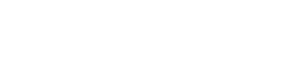

What is a novel anyhow? A reasonable question to ask your students as a semester goes along, since it seems to be a long form of prose that comes to dominate what we now consider literature. If one is to believe Amazon Rankings, then the most read forms of electronic books and the most purchased books remain novels (at least when I wrote this, but I’d be surprised if it changes). This wasn’t always the case and part of the history of the novel is its commercial success. Franco Moretti makes the case clear in his Graphs, Maps, and Trees where he argues that the rise of the novel can be studied using charts, as he does in his previous work Atlas of the European Novel (Moretti’s response, which is more useful.) Building on the idea of charting large-scale phenomena over time, he notices that novels rise (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 rises of novels from Graphs, Maps, and Trees

Something about the form, the markets, the people, or something else means that this particular literary form comes to dominate, so whatever time period you consider, it’s worth considering what was going on.

Its well established that the English novel rose first—the form seems to have been invented there—so even in a non-English classroom, it’s worth considering how those novels were imported into a broader literary discourse. Luckily, the text of most eighteenth-century English novels are freely available online. We have a fortuitous confluence of the intellectually important materials that have become technologically available (a careful reader will note that this is one possible explanation of the novel’s rise as well). But, how can you study the features of a whole genre? An easy way is to read them by putting them on your syllabus, which I encourage, but after reading them you can look back at the whole syllabus and chart the topics that come up.

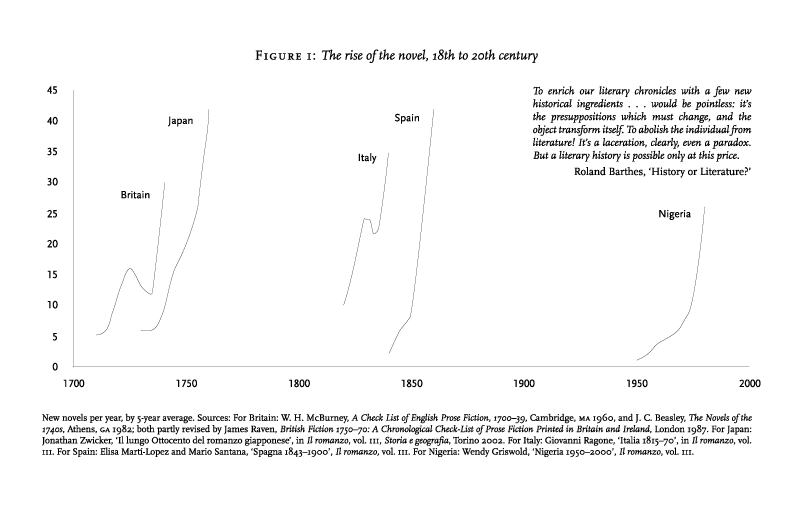

Fig. 2 Novel topics

To test this idea, I presented for Taylor Walle in her English 335 “Radical Jane: the Politics of Class, Gender, and Race in Austen’s ‘Polite’ Fiction.” Her course asked students to think about how English novels formed identities and related to the growing issues of British society. It seemed like a great chance to try some topic-modeling across her entire syllabus, the chart was produced with ten topics across the whole class (fig. 2). You can see the lesson here if you want to reproduce the work.

After demonstrating how the method works, we turned to this chart and looked for topics that crossed the texts. The works read for the class and on the chart—from left to right—are Emma, Northanger Abbey, Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, A Sentimental Journey, A Sicilian Romance, and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. You can see, and the class immediately saw, that the topics broke at the boundaries of books. You can see that many of the topics to detect specific books, but a few cross boundaries. Now, the topic used in topic modeling isn’t quite the normal sense of the word “topic.” It means a list of words with probabilities that, when they occur, signal the topic that is that list of words. The topics by their top words are,

time made heart letter moment feelings mind spirits happiness

present long felt thought affection left hope return day love

situation ...

elizabeth darcy bennet jane bingley wickham collins mrs sister

lydia catherine lady lizzy longbourn gardiner father family

netherfield kitty charlotte ...

miss mrs good great dear young make time room house give day

thought friend heard man home replied pleasure hear ...

julia marquis door ferdinand madame hippolitus castle heart duke

heard marchioness length appeared light night discovered time part

count scene ...

man life love woman character mind world society sense opinion

great beauty good present taste nature understanding husband

degree subject ...

emma harriet weston mrs knightley elton thing jane woodhouse miss

fairfax frank churchill body hartfield bates highbury father sort

harriet's ...

fleur paris monsieur poor hand count thou man set told madame good

french thy heart lady tis put made nature ...

elinor marianne mrs dashwood edward jennings sister willoughby

colonel lucy john mother thing brandon ferrars barton middleton

marianne's lady town ...

catherine tilney isabella thorpe morland allen general henry bath

eleanor catherine's brother james father street hour northanger

abbey john captain ...

women men reason virtue sex respect mind duties affection make

heart children power render human virtues true allowed till duty

...

As far as the course goes, the first topic seems to cover what all these texts have in common, but notice everything isn’t perfectly lined up by novel. The topic beginning “julia marquis door” clearly comes from Sicilian Romance, but also hits on some later chapters of Northanger Abbey. Why would that be? Well, if you know the texts, you realize that some of the same Gothic themes occur in both texts and they use the same words.—“Dear students, can anyone bring us to where in the text this happens?” And, we enter the realm of the normal literature classroom.

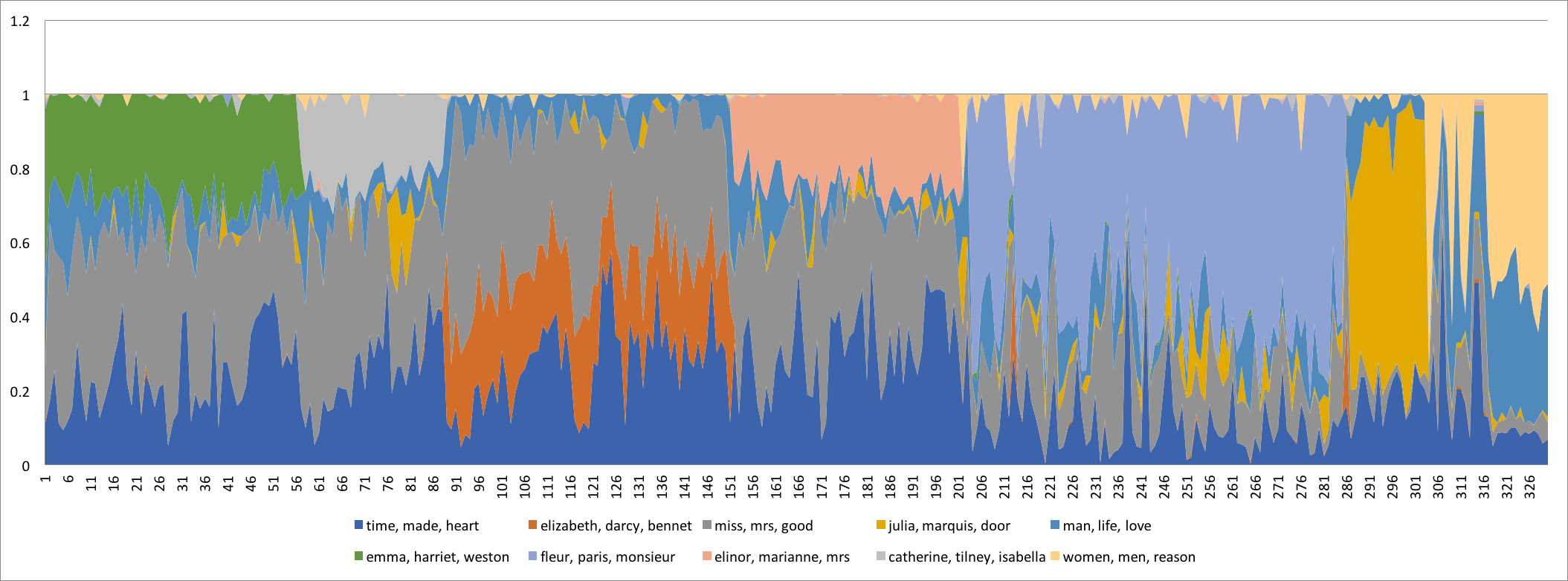

By presenting a broad view of the texts, built by a computer algorithm, but out of the words of the text, we invite students to re-read works. Not-reading becomes re-reading and presenting words across the entire corpus puts students into partnership with technology to ask what it is about the form of novelistic prose that makes it popular and speak to social issues. Furthermore, we also encourage students to be critical of the results of computerized analysis. Several students noted that these topics were obvious, having read the works, and that they could have come up with them by hand, which is—of course—true. It’s easy to scale these up beyond what you could do by hand, but seeing how they reflect what is accurately in the text shows that they provide some purchase on truth and also suggests what might be going on with other computerized analyses. One way we imagined it was that the computer applied an obvious rule at a fine level of detail. If we follow the same method, but only for Emma by paragraph, we get a much messier chart (fig. 3), but seeing that chart, students can begin to engage with both literary texts and computers that help them to not read—to ask what it means and what can be done with it.

Fig. 3 Emma by paragraph